ARE UFOs USING THE EARTH FOR A GARBAGE DUMP?

- December 12, 2017

- 0

By John Keel

SAGA Magazine

Spring had come to the quiet back hills of West Virginia and on the evening of Thursday, April 20, 1967 , three adults and two small children were sitting in front of their small bungalow on Plantation Creek Road, a narrow strip of ruts and mud holes a few miles outside of the little town of Pliny, enjoying the unseasonably warm weather. Suddenly, around 8 : 15 P.M., something came sailing out of – the clear, starlit sky and crashed to earth directly in front of them, barely missing a little three year old girl playing in the winter-brown grass.

“We could see for miles,” one of the witnesses told me four days later. ‘There weren’t any planes around. There just wasn’t any place for that thing to come from. And if it had fallen a foot off in any direction it would have hit one of us and from the way it hit the ground I’d say it would have really hurt.”

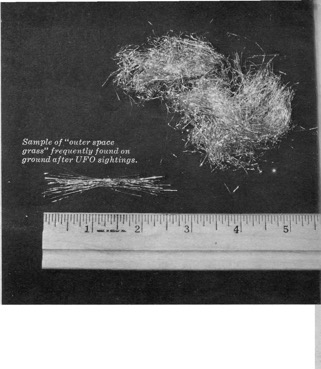

“The thing” was a large, tightly packed ball of finely cut metal foil which splatted against the ground with a loud thud and spread out over an area about two feet square . It must have been slightly larger than a softball before impact. The startled children gleefully pounced on the glistening mess, which resembled short strips of very thin Christmas tree tinsel. But their alarmed mother hauled them away from it. Within minutes, both the mother and the two children were covered with a red rash which they said lasted for several hours and itched fiercely. The men, disturbed by this reaction, feared that the substance might be radioactive so they covered it with a rubber door mat and called the State Police.

The next day Corporal R. W. Porterfield of the Winfield station of the West Virginia State Police drove into the hills, sought out the family, carefully collected most of the foil from the ground, and sent it off to the Criminal Investigation Laboratory in Charleston, W. Va. for analysis. West Virginia was in the midst of an amazing orgy of “flying saucer” sightings at the time and everyone was very interested in anything that appeared in the sky or fell from it. While roaming up and down the Ohio Valley collecting material on these incidents, I had also come upon several “falls” of this metal foil. I already had several samples of it in my brief case.

A large quantity of the stuff had been found spread over several acres of farmland on the Sand Road in Point Pleasant, W. Va., in November, 1966. Dozens of UFO sightings and several brief landings had been reported in that immediate area. Additional samples had turned up in Pennsylvania , Michigan, Indiana, New Hampshire, and several other spots where UFO sightings were especially intense. All of the samples were identical…very short (about two inches long) strips of shiny, silvery tinsel slightly wider than ordinary steel wool. In West Virginia they called this substance “outer space grass”, and in some places disgruntled farmers had to shovel it up before they could proceed with their spring plowing. It has a tendency to ma t in to clumps and fall in concentrated masses. Usually, it was found after one of those mysterious bobbing white and red lights had slowly and silently passed over. Such lights were as common as fireflies in the fall of 1966 and the spring of 1967. The most recent appearance of the strai1ge material took place in Amagansett, L.I., in early July, 1967. Several small piles of the foil were found there by Mrs. Bernice Lester and samples forwarded to the writer proved to be precisely similar to those collected in West Virginia.

Accompanied by Mrs. Mary Hyre, a jovial woman with 2 5 years of experience as the West Virginia correspondent for the Athens, Ohio Messenger, I interviewed the people of the Plantation Creek Road and learned that they, like so many others in the state, had been watching strange aerial objects nearly every night.

“We see these things all the time,” one farmer told us. “They look like big orange balls of fire. Guess they must be some of those satellites we’re putting up.”

That rang a bell. I remembered that two piles of this metal foil had been found at Lapeer, Mich. on December 9, 1965, shortly after numerous witnesses had reported ob¬serving a bright orange sphere which, they said, seemed to dump something out as it went by. (Incidentally, man-made space satellites appear as tiny pinpoints of light moving rapidly across the sky. They are most difficult to see with the naked eye unless you know the exact time and place and watch for them. ) Mounds of this material have also been repeatedly found in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania. And a few years ago layers of the stuff were found strewn over the greens and trees of a golf course near Camden, N.J.

Checking with other farmers living along that West Virginia ridge, Mrs. Hyre and I discovered that Mr. and Mrs. Charles Hudson had come upon a small quantity of “outer space grass” in their orchard only a week before that mysterious ball had plopped down on their neighbors’ lawn. It was, Mrs. Hudson pointed out to us, lying directly over a telephone line which was buried in that orchard. (Many telephone companies are now burying their lines instead of stringing them on poles.)

“We didn’t give it much thought,” Mrs. Hudson remarked. “Didn’t even botl1er to pick any of it up…until after that ball of it came down and very nearly hit the little girl.”

In the State Police station at Winfield, Corporal Porterfield said that there had been two small strips of paper mixed in with the samples he had collected. He described this paper as being extremely thin, unevenly cut to about four inches in length, with a glossy brown finish. Unfortunately, these pieces got lost somewhere along the way. Bu t Lieutenant R. J. Barber of the Criminal Investigation Bureau in Charleston ran a spectrographic analysis on the samples of the foil and on April 28 he revealed that “particles submitted are composed of aluminum and traces of magnesium.” The material was not radioactive or magnetic.

The results of his tests came as no big surprise. On September 7, 1956 , a large circular machine flew low over Chosi City, Chiba, Japan , and hundreds of people standing agape in the streets reported that it ejected enormous quantities of metal foil which drifted down over the buildings and parks.

One of the witnesses, a dentist named Masatoshi Takita, collected a large sample of the material and sent it to the Industry Promotion Association in Tokyo for analysis. UFO buffs around the world held their breaths, hoping that the long awaited “physical evidence” for the existence of flying saucers had finally been found . They were disappointed when the laboratory revealed that the foil was com posed of aluminum, lead, silicon, iron and copper, all rather mundane earthly materials. The pieces were four to five centimeters in length, 1 mm in width, and 10 micron thick…identical to the West Virginia samples. However, since hundreds of people had seen .the stuff fall out of a saucer-shaped craft there seemed to be little question about its origin.

Aluminum is not mined, but must be manufactured by extracting it from bauxite. A check with the Kaiser Aluminum Company in Hillside , N.J., and the Aluminum Association in New York revealed that the common aluminum foil sold by the roll in supermarkets consists of 99 % pure aluminum , with minute amounts of magnesium , zinc, copper, silicon , iron and other random impurities making up the remaining 1%.

Nothing very startling there. Unless, of course, the UFOs were buying aluminum foil in supermarkets, shredding it, and dumping it out all over the American landscape.

Since it has been repeatedly proven that this “outer space grass” is plain old Yankee aluminum, there is one other possible source for it. In his investigation into the mystery, Corporal Porterfield had called up the National Guard Air Force Base in Charleston and had been told that tl1e foil was “just ‘chaff’ that Air Force planes use to foul up radar on training flights”.

The explanation made sense and Corpora l Porterfield was willing to forget the whole business. Bu t I wasn’t.

On my way back from ‘Vest Virginia I stopped at the Pentagon in Washington , D.C. and confronted Lt. Colonel George P. Freeman , spokesman for the Air Force’s Project Blue Book, with the “outer space grass” mystery. Colonel Freeman, a placid, balding man with years of experience in Air Force Public Relations, has been struggling to restore the Air Force’s good image after the “swamp gas” fiasco of a year ago. He was most cooperative.

“We get a lot of this ‘chaff’ in the mail,” he admitted. “And we send it on to Wright-Patterson (headquarters for Project Blue Book), but it’s just the stuff used against radar on training flights.”

If that’s all it is, I asked, why did he bother to forward the mail samples to Wright-Patterson at all? Colonel Freeman stared at me wearily. Then I asked if I could see a sample of foil used by the Air Force for radar purposes. “We don’t have any of it here in the Pentagon,” he said. “You’d have to go to an Air Force base to get some.”

Fine, I responded willingly. I would do just that.

He patiently explained that I would be wasting my time. Soon after the development of radar during World War II, our planes began using strips of tin foil as a counter measure. This material was cut into long, wide pieces and packed in boxes. As our bombers flew over Germany, the gunners would periodically dump the boxes out of open ports. As the tin-foil fluttered down, the enemy’s radar beams bounced off it and it produced false images on their radar scopes. It was a reasonably effective counter-measure for a time but as radar became more sophisticated, this technique became obsolete. Besides, the rapid advance in the design of military aircraft made it impractical. The planes flew too high and too fast and there were no longer openings from which the “windows”, as the tinfoil was called, could be dumped.

By the time the Korean War rolled around, we had developed electronic gadgets that did the same job and did it better. All modern military planes are equipped with these “black boxes” which, according to an Air Force release, “are transmitters designed to radiate interfering signals which either block the receiver or obscure the targets on a radar scope, distort or deny the sound on radio, provide erroneous guidance signals to missiles, place false targets on radar scopes or alter the courses on navigation devices.”

Tossing boxes of tinfoil out of a lumbering B-17 is one thing, but throwing “chaff” out of a modern jet bomber hurtling across the skies at 800 miles an hour is something else again. Here’s what the Air Force says about that : “They (‘chaff’ strips) are called tuned or resonant devices. At the lower radar frequencies, these strips become excessively long. Because of this, they are not easily packaged or dispensed from modern high speed aircraft. In order to overcome this difficulty, a second form of reflector called ‘rope’ is employed.

Rope, unlike chaff, is a roll of thin aluminum foil or tape, several hundred feet long, which gives strong reflections at low radar frequencies when it unravels i n the air. These are called u n tuned or non-resonant devices. Modern packages of these expend able reflectors contain both rope and chaff. Since rope i s no longer packaged separately, the term ‘chaff’ now describes the complete bundle or u n i t of reflective material.”

In all of the cases in which these very fine and very short pieces of metal foil have been found, not a single piece of this “rope” has been discovered…nor even seen. Since it is packaged together, one might ask why these strips “several hundred feet long” have failed to come down. What’s more, the “chaff” samples picked up throughout the world stick together in clumps and would not disperse easily, no matter how they were released in to the air. The pieces are always found matted together and such clumps, regardless of length, would certainly fail to reflect radar in the manner presumably intended.

Colonel Freeman, at m y insistence, arranged for me to visit a secret radar installation in New Jersey where I could discuss this matter with experts. He asked the officers there to present me with some samples of the actual “chaff” and “rope” used on Air Force missions. So my next stop was at a setting straight out of a James Bond movie…a huge, windowless concrete building, surrounded by a high metal fence and heavily guarded.

An officer met me at the gate and escorted me through a labyrinth of empty gray corridors, past a gigantic chamber that looked like the War Room in “Dr. Strangelove”, and into a cluttered office where I was faced by a group of taut lipped officers and enlisted men. A young sergeant spread out a newspaper on a desk and produced a small, beat-up paper sack.

“You’ll never know what we went through to get this for you,” he smiled as he dumped the sack onto the paper.

“What’s so difficult about obtaining a sack of aluminum foil?” I asked. The stuff he had poured out was identical to my West Virginia samples, except that it seemed coarser and stiffer, as if it were very old.

“We have to find this on the ground,” one of the officers explained.

“Find it? I thought you fellows were dumping it out of your planes all the time!”

“‘We just keep this around to show it to trainees so they’ll know what it looks like,” the sergeant said.

I had the uneasy feeling that this was some kind of put-on.

“Well, how is this stuff packaged?” I asked. The spokesman for the group, a captain, looked at me blankly. “Does it come in boxes, or tubes, or cartridges, or what?”

“We can’t give you that information,” he answered warily.

“Then can you tell me how it’s dispersed?”

“I think they drop it out of a chute,” the captain said slowly.

“Fine. You have a lot of planes here. Could you show me one of those chutes?”

They looked at each other helplessly. I picked up a strand of the “chaff “. The whole clump stuck to it. “Since it sticks together like this,” I went on, “it looks like it wouldn’t disperse well…if at all. I’d like to know how you get it to spread out.”

“It’s released out of a chute,” the captain repeated.

“Is it packed in balls or what?” An air of silent tension settled over the group. “Is it wrapped in paper tape?”

“No…they don’t wrap it in tape,” the captain said unhappily. “It’s just dumped out of a chute.”

I started to gather up some of it.

“I’d like to take a sample of it,” I told them, “to compare with other samples.”

“We can’t let you have any of it,” the captain said quickly “It’s classified.”

“You mean you ‘classify’ aluminum foil?”

“The length of it can tell you the length of the frequencies our radar is using,” he muttered.

I held up a piece of it. It was about an inch and a half long.

“That’s a mighty short wavelength,” I noted. Nobody smiled. “Why don’t we take a pair of scissors and cut some of this up. Then I won’t be able to sell it to the Russians.”

I’m sorry. We can’t do that.”

“But the Pentagon promised that you would supply me with a sample.”

“I’m sorry,” the captain said. “This is classified material and I can’t release any of it to you.”

When I left that concrete wonderland, empty-handed, I was reasonably convinced that this “chaff” was as mysterious to the U.S. Air Force as it was to me. Since it was being found in such large quantities, it should have been a very easy thing for a major radar installation on an important Air Force base to produce fresh samples of both “rope” and “chaff”…if the stuff were actually being used by the Air Force.

The next day I called Major Hector Quintanilla, Jr., head of Project Blue Book at Wright-Patterson in Dayton, Ohio and asked him about “chaff”.

“We get a lot of it here for analysis,” he told me.

“Could you send me a sample, along with a copy of the results of your tests?” I asked.

“Oh, it’s nothing but tinfoil,” he declared flatly. “Tinfoil! Thanks a lot, Major. “I hung up. Project Blue Book was obviously right on the job. I mad e a note to send them a Gilbert Chemistry set for Christmas.

There are no regular Air Force bases in ‘Vest Virginia , only a couple of National Guard units, and , more important, there are no radar installations in the state and there fore there would be little purpose in clumping out “chaff” and “rope”, even on training missions. Reporters in West Virginia have failed to find any of this aluminum foil, in any condition, at the National Guard units.

However, there is a huge Kaiser Aluminum factory on the banks of the Ohio river south of Ravenswood, W. VA., which employs almost 5 ,000 people. Ravenswood is a hotbed of UFO reports. As a matter of fact, almost everyone there has seen at least one flying saucer in recent months. Man y have complained of the now familiar after-effect…burnt eyes similar to the results of staring in to a bright welder’s torch without wearing protective glasses. One resident, Mr. Lester Holly, has kept a careful log of local sightings. According his records, unidentified flying objects buzzed Ravenswood on March 1, 7, 9, 10, and 17, and April 15 and 17.

More important, scores of employees at the Kaiser Aluminum factory have reported a long string of fascinating incidents. I spent two days snooping around the immediate area and interviewed many of the workmen. Since Kaiser is involved in making classified parts for military airplanes, and since the Air Force allegedly informed the plant’s management that the objects reported were nothing more than stars and good old reliable “swamp gas”, these witnesses were all afraid to allow their names to be published .

One Kaiser Employee claims that he was driving a truck out to the garbage dump behind the factory one night in the middle of March when his engine suddenly quit, his radio went dead, and the ground around him lit up with an eerie glow. He climbed out of the cab and looked up and was astounded to see a large, brightly illuminated disk hovering directly above him. He ran all the way back to the factory in near hysteria and refused to return to his truck that night. Numerous other workmen have repeatedly reported seeing low-level UFOs around that garbage dump as well as above the factory’s water tower and over the factory itself. They tell the story of another man who quit his job on the spot one evening after watching three small reddish circular objects join a large, luminous cigar-shaped thing directly over the plant.

I visited that garbage dump to see if Kaiser Aluminum was throwing away any waste products or shavings which might resemble “outer space grass”. But all I found was garbage.

So we are still left with the mystery of the aluminum strips. While the Air Force is trying to take the blame, they can’t produce any proof that they are using these tiny strips, nor can they present a convincing case for the possible need of such material in the modern Air Force. On the other hand, if the UFOs are clumping “chaff” all over the landscape, why? Are these things the curious by-product of some unknown manufacturing process going on in our skies? If so, why don’t the mysterious UFO pilots-if they are the culprits-clump their garbage in the remote forests of Canada or the vast desert wastelands of the Middle East? The farmers of’ West Virginia are tired of cleaning up after them.