Did Pennington Build the 1897 U.S.A. Airship?

- December 19, 2017

- 0

Speculation as to the origin of the ‘Airship ‘ reported over the Central States of the U.S .A. in 1897 has resulted in many theories and at least one of these attributes the sightings to the activities of a peculiar antique sort of U.F.O. I understand that the reason that the craft looked very much like the current airship design already flying in Europe is that the U .F.O. denizens wished to present their ship to the natives in a manner that would be acceptable and understandable. However the airship in question did not seem to be at all anxious to present itself, operating as it did almost exclusively by night and skulking during daylight hours in and out of the way places.

Before accepting such ‘way out’ theories it would seem necessary to exclude any possibility of the machine being the production of some far-sighted inventor with the ability, wealth and resources to build and fly such a machine and also to keep the whole project secret.

Witnesses of the airship were often men of excellent reputation for veracity and often crowds of onlookers were able to compare experiences.

The descriptions tallied to a remarkable degree. It seems clear also that some of the sightings of night flying objects were of quite a different category and to present day ufologists may be recognized as being the result of ‘normal’ U.F .O. activity.

From the reports still in existence, it is possible to build up a very good idea of the type of dirigible involved and there is no doubt that in many respects it was similar to airships already built and flying in Europe particularly in France. In 1884 Renard and Krebs devised and built an electrically propelled airship called ‘La France’ which made a circular flight of five miles at its first appearance.

It would indeed have been strange if there had been no parallel activities in the U .S.A. at that time. Resources of material and money were there in abundance and among the fertile brains of rapidly growing scientifically orientated community was there no person of sufficient genius engineering ability and wealth to take up the aerial challenge?

I believe there was and I believe that his name was Edward J. Pennington.

Pennington was born in Franklin Indiana in 1858 and as a boy showed remarkable engineering aptitude and as he developed into manhood he displayed remarkable initiative, charm and persuasiveness. With these attributes it was not long before he

was running his own factory and at the age of twenty-three had patented a reciprocating head for planning machines the first of a continuous stream of patents which flowed from his active brain until his death in 1911.

He was ruthless too and could exhibit considerable showmanship in order to further his ow n ideas. A characteristic of Pennington which in this context is significant was the secrecy he achieved to protect his projects and his habit of quietly dropping one idea in favor of another with little regard to the financial outcome.

By 1885 Penington had acquired sufficient capital to set up the Standard Machine Works in Defiance, Ohio and two years later he created two further firms to make pulleys and wood-working machinery. A flood of Pennington Patents were registered at this time at Fort Wayne.

There were rumors of a company capitalized at one million dollars in Oswego, Kansas and another at Cincinnati with factories to produce ‘Freight Elevator s’. (Could this phrase possibly have been a euphemism for load-carrying Airships?)

After a brief appearance at Edinburg, Illinois, where he collected some 50,000 dollars from the in habitants for yet another ‘pulley works’ he came to rest at Mount Carmel, Illinois i n 1890 .

Now things begin to develop…this new Company was actually a four cylinder radial engine. . .”for the propulsion of an aerial vessel”. He also let it be known, that he was “readying a vessel to fly from Mount Carmel to New York “.

In 1891 he exhibited a captive airship some thirty feet long and six feet in diameter. It flew in a circle propelled by an airscrew turned electrically. The current was conveyed by wires in the tethering cable.

In 1893 he turned his attention to motor driven vehicles and again a spate of patents flooded from the Pennington brain. Soon he was making motor-cycles in Cleveland, Ohio and h ere he invented the first balloon tire.

Such giddy progress was bound to meet with reverses and due to h is dogmatic attitude and ruthless decisions he began to make enemies: yet his uncanny instinct for avoiding trouble kept him from falling foul of the law.

During 1894 he joined Thomas Kane who made kerosene engines widely used in dairies for milk separation. This event is most important in this thesis which will be evident later. Here, in Racine on the shores of Lake Michigan, they financed a really large concern for the development of petrol engines.

They patented among other things an ‘electric igniter’ for petrol driven engines which was really the first sparking plug, in 1895. In this year Pennington visited England and took some of his vehicles with him.

Exercising his well-known assurance and charm he persuaded Henry J. Lawson a successful manufacturer of bicycles to purchase patents to the tune of a half a million dollars. He was still here in 1896 and entered the Brighton Run. After an altercation with Mons. Leon Bollee his claim to have won the event was not disputed. After this he participated in the aerial demonstrations in the U.S.A late in 1896 and during 1897.

In December 1895 he had deposed with the American Patents Office the design for full sized Airship. Many of the features of this design are so close to those described by witnesses of the aerial ship seen in 1896 and 1897 that on this evidence alone one would suspect that Pennington could have been responsible.

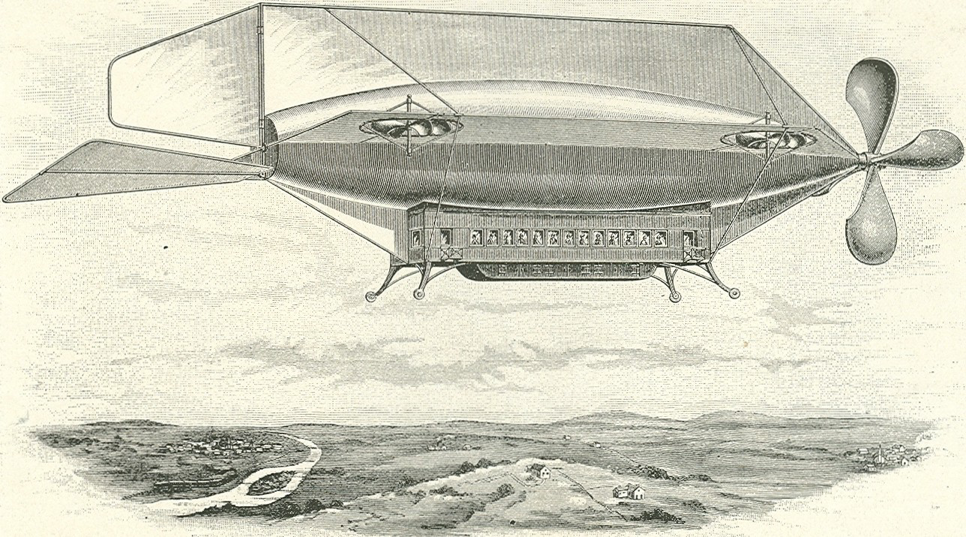

Basing the scale of the design on the size of the passenger seats the overall length of the ship would be about 140 ft. The keel beneath which provided accommodation for the crew and passengers, also housed large batteries and extended for 70 ft. with an equal amount of overhang of the envelope at each end. At the front end of the envelope a large airscrew about 50 ft. from tip to tip provided traction. At the rear an ample rudder and a horizontal fin allowed control of direction.

At the sides two horizontally disposed propellers furnished lateral ‘trimming’. Along the top of the ship a high dorsal fin would help to prevent sideways drift and yawing at slow speeds. Altogether a very impressive aeronautical design for that period of time.

It is probable that the finished airship based on this plan would deviate in minor details. Perhaps laterally placed aircrews were found to give a better lift and control if suitably shaped.

Wings or large ailerons above the envelope would also help to provide lift if suitably angled. ln 1895 during his motorcycle phase Pennington was heard to remark: “Suppose I have a cycle, screw driven, making a mile a minute…just suppose that…then suppose that I put aero planes on that machine…and they are under good control, what then ?”

What then indeed, the Wright Brothers would have been forestalled by several years.

The sighting of the Airship on the ground in 1897 by Captain Hooton at 6 p .m. on about 20th April is usually regarded as a true account of his experience which he recounted in the Little Rock, Arkansas, Gazette. He was, he said, out hunting near Homan when he heard the sound of ‘pumping’ like the noise of a Westinghouse locomotive brake.

Going in the direction of the sound he was amazed to behold “the famous airship” in an open space. A man wearing dark glasses was doing something at the rear of the ship. As he approached four other men appeared.

During the ensuing conversation, there was no doubt in his mind that the crew were American. When the ship was ready, three large ‘wheels’ started to rotate on either side of the airship and with a hissing sound she took off. The ‘aeroplanes’ on top of the envelope sprang forward and the ship rapidly gained height and speed. (For a more detailed account of this sighting please refer to the JULY/AUGUST 1966 issue of The Flying Saucer Review.)

The ‘pumping noise’ is of great significance. This noise is noted in at least three of the sightings. Twice it was referred to as being similar to that made by a milk separator. This is almost conclusive, it was Thomas Kane whom Pennington joined in 1894, who made the motors for these separators.

All witnesses agree that there were lights aboard in abundance with our very bright searchlight which was seen to dim as the airship accelerated.

One witness encountering the aeronaut grounded claims to have asked why he turned the light on and off so much. He replied, no doubt truthfully that it consumed a great deal of motive power. We are led to the conclusion that Pennington’s ship was propelled by a petrol-electric, or diesel-electric system. A bank of large batteries would be charged by a motor driven dynamo and would then operate electric motors geared to the airscrew (s). This system was widely used for the propulsion of road vehicles in the early years of this century.

After a trip of some miles it might be necessary to land to recharge batteries. Such a propulsion system would be well within Pennington’s capabilities at this time.

The crew referred to by some witnesses included a woman, and it was customary for Pennington to take his wife on most of his exploits. (He married three times but I cannot find record of any children.)

Also a bearded man.

I have a photograph of Pennington with one of his vehicles and here he is accompanied by a man with a beard. Pennington himself was tall and of good physique. He usually sported a rather long dark mustache.

The next evidence required toward proving that the ship was not only terrestrial but Pennington ‘s, is to plot the course of the airship from recorded sightings during the !voyages’ of 1897 and to show that its speed was within the capabilities of such an early craft and that it operated in the vicinity of Pennington workshops.

Here I suggest the reader obtain a good large scale map of the central States of America. Those included in the Encyclopedia Britannica of 1911 are most useful being nearly contemporary.

Two series of sightings occurred in 1897. Expedition One. Starting from Pennington ‘s base at Oswego, Kansas, to Belleville, Kansas, to arrive March 25th , thence to Sioux City some 200 miles northward travelling at night. Making around 40 mph and in fair weather the six or so hours of darkness would allow easy arrival by 28th March. Here the ship landed and charged batteries?

Turning southward an easy night run of 100 miles allowed late worshippers leaving church at Omaha, Nebraska to view the aerial visitor. Continuing via Lincoln and Beatrice on the southerly run arrival at Everest, Kansas on April 1st. another 100 miles apart. In fact Kansas City was reached quite early at 8:15.

Back to base at Oswego without serious mishap on about the 3rd. April?

After this there are three possibilities:

a) Pennington flew to Racine on Lake Michigan by April 9th keeping to out-of-the-way landing sites.

b) The ship was partly dismantled and carried by rail in Pennington’s closed rail cars to Racine.

c) That Thomas Kane had another similar airship at Racine.

I would suggest (b) as being the most probab1e in t he circumstances. Pennington h ad the resources and the experience in moving large objects by rail from place to place, vide his captive airship which was shown at exhibitions at Chicago and elsewhere.

Expedition Two. The Airship would have taken the air on the evening of April 9th 1897 and leaving Racine some 60 miles from Chicago was seen first north of the city and then to south-east at 9:30 p.m. Passing over the lake.

Turning westward the ship would have reached vicinity of Eldon in Iowa some 200 miles after five hours at around forty mph. Spending the day of the 10th on the ground at some secluded spot the batteries would again be charged and ready for the take-off on the evening of April 10th. Then passing over Eldon westward to Ottumwa (10 miles) at 7:25 and 7:40 p.m . respectively, the ship is seen near Albia 25 miles further on at about 8:10 p.m. This chain of sightings allows some estimation of the airship’s speed-35 miles in 45 minutes which is better than 45 mph. Wind speed must be taken in to account but from the sighting reports the weather during this period seem s to have been remarkably calm.

Steering now toward the north-west apparently en route for Racine, the ship would have passed near Mount Carroll but the date given for the airship over this city is April 9th. One must conclude that if t his date is correct that the craft passed over this city on the westward leg of its journey before turning south-east toward Eldon. This is perfectly possible on the time schedule estimated.

However , and here one must speculate on Pennington ‘s movements, it is not certain how the airship arrived at its next point at Yates Center, Kansas on April 19th. It could well have travelled at night over the next week or so southward which would be well within its 40 m ph capabilities. Or it may have returned to Racine and have been once more despatched by rail.

At Yates Center there was the unfortunate incident of a young heifer becoming entangled in the mooring rope on takeoff. Then south east and a fairly long haul – 400 miles – to near Texarkana, but at 40 mph only ten hours of darkness were necessary. Here the ship was obliged to land on April 21st. to recharge batteries. In the evening when all was ready for take-off the airship was spotted by one Captain J. Hooton whose detailed report is well known.

Airborne again and travelling in a leisurely manner Hot Springs, Arkansas was reached on May 6th. Once more the ship landed and was encountered by the Law Officers, Constable Sumpter and Deputy Sheriff McLemore. Both these gentlemen have sworn affidavits to their evidence in which they tell of a bearded mechanic and a young woman. There was also a young man who was engaged in filling a water bag. They were informed that the ship was en route for Nashville, Tennessee. This may well have been so, b u t I feel that it was not long before it was once again safely at Oswego, Kansas with Pennington highly satisfied with his aerial exploits. There is little evidence of its re-appearance.

From the foregoing evidence it must be conceded that the itinerary allowed by the 1897 airship was not particularly miraculous even for a craft of that period, only it took place in America where hitherto no such aerial exploits had been seen. No wonder then, that the onlookers became scared and confused, suspecting a work of the Devil. The only Devil responsible was in my opinion one eccentric, brilliant inventor name Edward Joel Pennington.

Of course there are so many questions left answered. For instance why did Pennington decide to drop the whole project just when fame and fortune might seem to have been within his grasp? I would suggest that he was clever enough to realize that his airship, though a very remarkable invention had very severe limitations which could not readily be overcome.

There would be little prospect of increasing the battery capacity without making the ship larger and unwieldy . I t was obviously very much a fine weather craft and he had been extraordinarily lucky to have had such a long spell of fine, calm weather for his trials.

Also, he would have realized that until the internal combustion engine could be improved considerably in size and reliability the w hole airship project had better be shelved. The new and more financially rewarding field of the motor car must have seemed to Pennington to offer much better prospects of immediate financial rewards. He must also have known that there were aeronautical designers in Europe w h o had forged ahead in the airship field with whom he could hardly compete.

In the Motor Museum in Beaulieu, Hampshire there is a very rare vehicle. It is an 1896 Pennington motor tricycle. It is worth looking at closely. The twin cylinder, water cooled engine functions by fuel injection and the ignition system is remarkably ingenious, operating an early form of spark plug on each cylinder. The wheels have wire spokes and furnished with wide tires of modern cross section. It is a really remarkable piece of advanced engineering for its time and marks its designer, Pennington, as a brilliant engineer of foresight and genius.

THE ILLUSTRATED AMERICAN.

EDWARD J. PENNINGTON promises that an experiment with his airship shall be made very shortly. One of the machines is being completed at the works of the airship company at Chicago Heights.

Mr. Pennington is an aviator, that is, according to the definition by O. Chanute, one who points to the birds as indicat ing the way to success in aerial navigation, who believes that the apparatus must be heavier than the air, and who hopes for success by purely mechanical means. An aeronaut, on the other hand, is one who believes that success is to come through some form of balloon, and that the apparatus must be lighter than the air which it displaces. European engineers are generally aeronauts. The French have obtained measurable success. They have driven navigable balloons fourteen miles an hour, and Mr. Chanute thinks it is probable that speeds of from twenty-five to thirty miles an hour, or enough to go out when the wind blows less than a brisk gale, are even now in sight. Very much greater speed is not likely to be obtained with balloons, for lack of sufficiently light motive power, and because of unmanageable sizes. It is stated that the German, Russian, and Portuguese governments have organized aeronautical establishments for war purposes, and are experimenting in secret. It may be remembered by our readers that upon the recurrence last spring of the annual European war scare, a story came from Warsaw that a German war balloon had been seen hovering over the Russian frontier, and that it seemed under perfect control. Fact or fancy this may be; it is certain that the Austrian army had a tolerably efficient balloon service.

American inventors, traditionally bolder and more original than their European fellows, have been seeking to penetrate the secret of the birds. The interesting experiments of Hiram S. Maxim and Prof. S. P. Langley indicate that they may succeed in constructing a flying machine with aeroplanes. Throw a piece of cardboard through the air, and you will see what it is hoped to accomplish with aeroplanes.

According to the published accounts, the Pennington airship is constructed entirely of aluminum, this metal being used on account of its lightness, strength, and ductility. The main part of the machine is the buoyancy chamber, which is shaped like a huge cigar, is 12; feet long and 38 feet mean diameter, and is calculated to be capable of lifting a weight of two and one-half tons. In it there are two compartments, one of which is filled with hydrogen gas, and the other contains the machinery. Along the entire length of the chamber extend, on top, a vertical fin, which should help to propel the machine like the sail of a ship, and, at the sides, horizontal aeroplanes. To the tin and to the aeoroplanes are attached rudders, to steer the machine to right or left, and up or down. Under the ship is the car for passengers; it is of aluminum and has cushions filled with hydrogen gas. I t weighs only 235 pounds. A car of the same size, constructed with ordinary materials, would weigh 1,880 pounds. The fin and the aeroplanes are hollow, and are filled with hydrogen.

The airship is to be propelled by a screw placed in front. It has four spoon-shaped blades. Motive power is furnished by two engines, each with four cylinders. The piston rods are attached to a single center, and act reciprocally. They are driven by hydrogen gas exploded by an electric spark. The engines are of aluminum, are very light, and are said to be wonderfully powerful.

In each of the aeroplanes at the sides of the chamber are two screws which will be used in elevating or lowering the ship.

The first airship is designed to carry ten passengers. Mr. Pennington’s plan is to begin by sailing over Lake Michigan to Chicago the first day. Then he will set out for New York City, New Orleans, and San Francisco.

The speed of the ship is as problematical as her ability to sail at all. Aviators think, however, that a speed of sixty or seventy miles an hour can be obtained without much trouble as soon as the preliminary problem of how to fly has been solved.

THE PENNINGTON AIRSHIP

This vessel is now being constructed at Chicago Heights, Ill., and advertised LO tart for New York in October. This machine is guaranteed to fly at the rate of seventy.five miles an hour.

AREA’S OWN AIR SHIP PROVED TO BE A WONDROUS HOAX: ONLY THE MODEL FLEW

From The Valley Advance, Vincennes, Ind., April 8, 1980 By Richard Day, Byron R. Lewis Library staff member

THE GREATEST WONDER OF THE AGE!

An advertisement in the Chicago Tribune of Feb.8, 1891, called the Mt. Carmel airship. The Greatest Hoax would have been more accurate. The airship was first reported in the Vincennes Weekly Commercial of Oct. 31, 1890. The Mt. Carmel Aeronautic Navigation Company had been formed at Chicago on Oct. 22 for the construction “at the earliest possible moment” of a large airship designed by Edward J. Pennington and Richard H. Butler of Mt. Carmel, Ill.

Capitalists from Chicago, Grand Rapids, Columbus, New York, and Birmingham, England, were going to invest an alleged 20 million dollars in the scheme. Work would begin at once on a plant at Mt. Carmel.

The company letterhead pictured monster machine-shops and factories, “beside which the McCormick reaper-works or the rolling-mills of South Chicago would look like coal-sheds.” The Mt. Carmel airship, according to Pennington’s description in the Nov. 10 Weekly Western Sun, was to be 200 feet long, but made entirely of that new wonder-metal, aluminum, so that its total weight would be only 4,200 pounds.

A cigar-shaped cylinder of aluminum, one-hundredth of an inch thick, and containing 100 buoyancy chambers filled with hydrogen gas would enable the ship to carry a ton of cargo. Along the sides of the buoyancy chamber wings would extend, forming parachutes to assist in descending. Four electric-powered propellers in the corners of the wings would raise or lower the ship.

Steering was to be by a rudder running along the top of the lifting chamber, with another rudder at the tail for up-and-down direction. A passenger coach suspended below would hold 40 passengers and a pilot, who could control the ship by electric appliances.

In front, a large four-bladed propeller powered by a gas engine would drive the airship up to 250 miles an hour.

“Within three weeks we will sail into Chicago in the first of our airships,” Pennington told a stockholder’s meeting at Chicago, according to the Dec. 19 Weekly Commercial.

Pennington, a “neatly-dressed, intelligent and studious-looking man,” said the ship would make its trial flight from its place of manufacture at Mt. Carmel to St. Louis, from there to Chicago, and thence to New York, carrying a half-dozen reporters and any of the stockholders who wished to accompany him.

Soon, however, disenchantment began to set in. The Dec. 26 Western Sun said that only a 24-foot model would be displayed at Chicago, to be replaced in three weeks by the 200-foot ship, which would fly from Mt. Carmel to Chicago in one hour. The Jan. 16, 1891 Western Sun printed the text of an agreement by which Pennington sold the right to exhibit the 24-foot model at Chicago for $100,000.

“But we expected to see the original flying by this time in the open air,” complained the Western Sun.

The following week Pennington tried to reassure the press and his stockholders that the full-size airship would soon be ready.

“All the parts of the large machine, which will carry 40 persons, are on the ground at Mt. Carmel,” the Western Sun quotes him as saying, “and we shall put them together at once.” He also claimed he had been sick for the last two months, and had received bad publicity in some newspapers, whom he was considering suing for “liable” (sic).

“Have you ever sailed through the air with your ship, Mr. Pennington?” asked a reporter from the Chicago Post.

The inventor looked surprised.

“Why, no,” he replied, “But then, you know, I am not an aeronaut.”

The same issue of the Western Sun reprinted a satiric letter from Mt. Carmel to the Chicago Post, purporting to explain that the cause of the delay was modifications in the

airship–which the writer renamed The Vibrator–to increase its speed from 200 miles per hour to 200 miles per minute, thus enabling it to fly to the moon in eight to 10 hours.

“A little fishy” was the headline story in the Jan. 30, 1891 Western Sun, reporting that the model airship had arrived at Chicago, but shipped by railroad express in a box, not flown from Mt. Carmel.

“This airship,” said Pennington, “is only thirty feet long, and is a duplicate of the larger ones. It will carry about 120 pounds, and hence is not large enough for passengers.”

The large box contained 965 pounds of silk and rubber bags made in New York. “The gas chambers of the large ships are of aluminum,” explained Pennington, in a dead-level monotone, “but those of the model are of silk, because we could not get the chamber finished.” This would not make any difference in the test, however, because the airships would be guided automatically, by an electric compass connected to the rudders. Pennington was unable to answer Chicago reporters’ questions about the size of the large ships or amount of cubic feet of gas necessary for them–he had forgotten the figures. “The company has nothing to do with this working miniature which I have in Chicago,” he said. “It is a side issue of my own.”

“But he did not say,” noted the Chicago Times, “why a man who was at the head of a company with $20,000,000 capital, and who was engaged in building airships which will mark the greatest epoch in human achievement, should embark in a side-show and exhibit an incomplete and useless mode as a freak is shown at a circus.”

“The railroads are agin me,” said Pennington in his low monotone, “and don’t overlook no chance to run me down.”

The Mt. Carmel Airship went on exhibit at the Chicago Exposition Building on Feb. 2. Admission to see the demonstration flights was 25 cents.

True, the airship only rose 25 feet in the air and flew in a 100-foot circle at the end of a line. And true, the three-quarter-horse-power engine could only turn the two-blade propeller at 42 r.p.m., and drive the ship at a top speed of six miles per hour.

But thousands went to view the flights, and “at the close of each demonstration the enthusiasm is spontaneous and earnest, and loud applause resounds throughout the vast hall.”

The Times grudgingly commented, “One who can work up a scheme whereby 500 to 1,000 people per day are induced to separate themselves from 25 cents each to see an airship which resembles an exaggerated link of bologna sausage, traveling a limited

circuit of 100 feet is entitled to be called a bird. He may lack feathers, but he is entitled to them all the same.”

The final blow for Pennington’s airship came in the March 7, 1891 issue of Scientific American quoted in the March 13 Commercial with the headline, “Airship Exposed.” A

full-page article, accompanied by a large picture of the “machine,” declared Pennington’s airship a failure.

It said that the art of flying in the air by mankind had not yet been learned, nor the means thereto invented. The article spoke of the airship as a “deceptive and visionary scheme, lacking the essential elements of a flying machine. As a thing promising in the way of aerial navigation, it is without value.”

The last ad for the Mt. Carmel airship appeared in the March 17, 1891 Chicago Tribune.

CHICAGO NEWSPAPERS ran the ad at left to announce demonstrations of the Mt. Carmel Air Ship. Those who paid their quarter were enthusiastic, despite the small size of the model which Edward J. Pennington actually brought to the exposition Building.

The full-scale version, he said, would hold 40 passengers and go as fast as 250 miles an hour. The engraving shows the cigar-shaped body, the rudder along the top of the cylinder, two of the propellers which would lift, and the larger propeller to drive the craft. The lettering along the passenger gondola reads Mt. Carmel Aeronautic Navigation Company.